When I was asked to speak on innovation in Khadi, I immediately went back to Annapurna Mamidipudi’s research on the subject. I had read an informative article written by Wiebe E. Bijker and her on ‘Innovation in Indian Handloom Weaving’. In this, they discuss and share a case study on ‘Uppada Jamdani’ where weavers innovated by working backwards to seemingly less sophisticated techniques. Innovation is often times associated with something technological, although innovation simply means ‘a new method, product or idea’. Inspired by her work, I presented Gandhigram’s case study on innovation in Khadi.

Aditi Jain

Representing Gandhigram Khadi & VIPC Trust

Presented at the International Conference on Globalization of Khadi, Jaipur

January 31st, 2020

Growing up I’ve heard stories from my naani of how her aunts and grandmothers used to spin on the charkha to sell the yarn they make. ‘Athiyo kathyo aur ghar chalayo’ she fondly recalls. I’ve heard similar stories over the last few years from patrons and well wishers of Gandhigram too which led me to believe that most indian families have some sort of historical connect to khadi. Of course Gandhiji has a pivotal role to play in that.

But what has also been a common perception amongst a vast majority is that khadi is “old fashioned”, that it is for the older generation.

Over the last decade, we have seen some fantastic brands emerge who have taken khadi to another level and have worked hard to give it a new position.

A luxury category.

A fashion statement.

Khadi has become aspirational.

At Gandhigram, we are now part of that larger dream to make khadi more accessible, and relevant to our current times. To achieve this we had to get creative. We had to innovate. Innovate by creating something new while keeping intact the traditional practices and knowledge.

To give you an example, I’d like to present a case study of how our stoles came into existence.

At Gandhigram, there was a large production of khadi towels. These are simple, plain weave, space-dyed towels – popularly known as firefly towels because of the pattern that space-dyed yarn creates. Now the demand for these towels had reduced. While we had to strategise a new marketing plan, we also wondered ‘what else?’ ‘How else do we tackle this?’.

And by this time, we had started interacting with a younger market whose requirements were very different. We had to think of a way to keep the looms busy while making products that would be marketable as well. This is how the stoles at Gandhigram came into production.

Idaikkal is a cluster in the Thirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu where some of our towels were being produced. Mr Prasath, the production manager, and I brainstormed ways to address this problem statement.

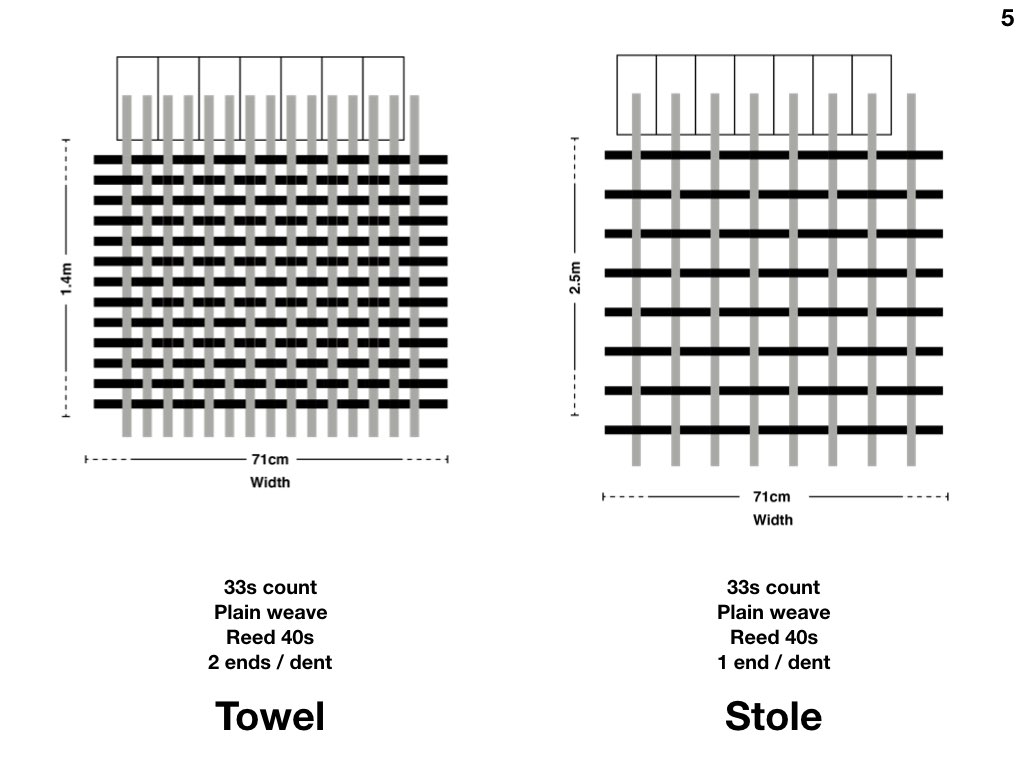

Here’s some technical info to explain. Hope this visual makes it a little clear.

The towels are 33s count, plain weave, 2 ends per dent, 71 cm width and 1.4 m.

Now, the constraints we were working with, we can’t change the loom structure, so the reed remains the same & the width of the fabric cannot increase.

What we could change was the denting / EPI. We reduced it to 1 end per dent, and increase the length to 2.5 m, keeping everything else the same, and now we have a light weight stole. Figuring out the technicality was the easy part.

The real challenge came in implementing this. Most of our weavers have been with us for decades, and for them to suddenly change the basics was a mental discomfort. We visited them regularly and tried to understand their apprehension and convince them to just give one warp a try. We of course provided them a better wage structure. One weaver finally agreed to amuse us. To reduce the strangeness of our request, we kept the firefly design the same so to them it was just a longer light weight towel. Here are images illustrating what I mean, and a closeup to show you the texture.

The first batch of stoles were an instant success. The weaver too found it easier to weave and was excited to keep it going. In an attempt to keep them engaged and involved in the process, I would plan the warp pattern and leave the weft way interpretations upto them, and I was pleasantly surprised to see some interesting compositions. We also made a batch in naturally dyed, karungani desi cotton stoles for Swaminathan of Kaskom. We reached a real milestone, when another weaver came to us wanting to produce the stoles.

Through this exercise our learnings are multifold.

First. Innovation is generally associated to technological changes, but innovation is working within the constraints with simple changes and creating something new.

Second, the idea of “new” is itself contextual. Stoles are being produced in other khadi institutions as well, but given the background of Gandhigram, it is a completely new addition for the organisation and the weavers.

Third, for anything new to be implemented there will be an initial resistance, persevering through that makes the whole journey worthwhile. This whole process from idea to seeing the first batch of stoles took us about 6-7 months.

I’d like to close by saying Khadi is now gaining global relevance, especially with the slow fashion and sustainability movements and as long standing khadi organisations, it is our responsibility to keep challenging ourselves and innovating to stay relevant and to keep this going.

Thank you.

Mamidipudi, Annapurna & Bijker, Wiebe. (2018). Innovation in Indian Handloom Weaving. Technology and Culture. 59. 509-545. 10.1353/tech.2018.0058.