Back in 2014, I visited Udaipur with my friend, Samiksha. It was our first year at NID and we were enthusiastic about travelling to nearby places. Off we went, on a bus journey, with no itinerary but a willingness to explore and the ultimate craft resource book – Handmade in India.

We started our journey from the ‘City of Lakes’. Udaipur is truly a beautiful city, complete with narrow lanes, local food and tourist spots.

We had read of Danke ka kaam, that is practiced in Udaipur and found a contact on facebook and went to visit them. Mustan Zariwala, the artisan, says embridery is part of the family’s traditional occupation. He opened up his workspace for us to observe how they plan the design and embroider.

The word ‘dank’ in jewellery making is a reflective foil made of thinly beaten silver or gold sheet. It has a concave shape making it quite unique. This kind was mostly used for select articles that were part of the wedding trousseau, but now they use silver sheets with gold plating or other cheaper metals.The low prices enables them to cater to a wider audience now. Earlier, rich fabrics like silk, velvet and satin were used, which have now transitioned to chiffons, tussars and even synthetic fabrics. There seems to be only one family currently engaged in the work with artisans of the older generation. It is largely practiced by men, although women sometimes aid in making the dank.

The embroidery is done on a wooden frame which varies in size from 6ft x 3ft or 4ft x 2ft. The tools they usually are – needles, crewel needles, spool to wind the silver thread on. The design is drawn on a butter paper and once the fabric has been stretched on a frame, the marking is done using chalk. The dank is placed in position and a needle is drawn through it and the fabric. About 7-8 strands of plied metal wire (kasab / badla) is couched along the dank to create designs around it. The patterns and motifs are mostly florals, creepers, peacocks, paisleys, jalis and geometries.

What I found most intriguing was how repeating one shape leads to a variety of motifs and patterns. Something that starts off with a simple geomtery takes the form of elegant stylistic designs..

Tools of the trade – scissors, kasab wound on a spool, needles, thread, white chalk

Tools of the trade – dank placed on a cloth mat. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

Mustan bhai’s workshop with two wooden frames in use. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

A smaller frame for small sized items like dupattas. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

Artisan working on the border. The dank is attached first, then the pattern is made around it using multistrand yarn.

Stitching the dank to create the basic form. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

A dank with couching done around it. Couching protects the concave dank from flattening. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

Couching around the dank with the kasab (multi-strand thread). Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

This is done in a continuous manner to maintain a neat finish. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

On the right shows the dank attached to the fabric and the pattern imprinted using chalk. The left shows the couching around the dank. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

A ghaghra-choli set embroidered with danka by the artisans. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

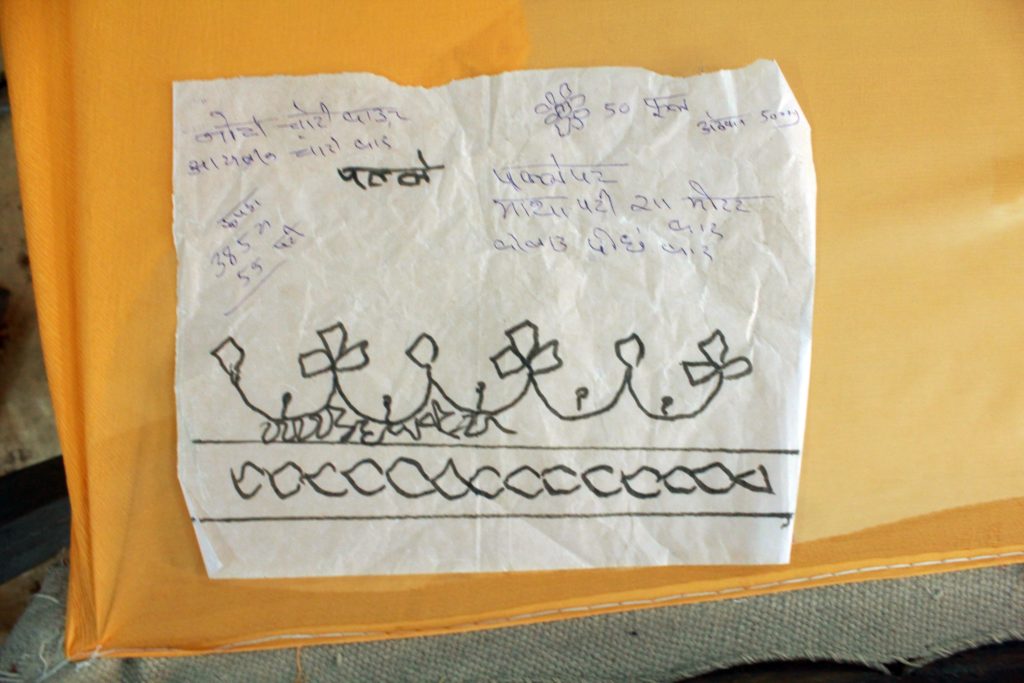

A sketch of the design with notes.

A popular motif in danka is the peacock.

This is the stencil they use to transfer the design to the fabric. Piercings are made along the lines, placed in position and coloured in to transfer the pattern.

Unstitched skirt panels embroidered with danka in paisley motifs and jaal pattern. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

Variations of the peacock motif.

Planning the design placements for blouses and saree. Image Courtesy: Samiksha Singh

Panels of a skirt densely embroidered with danka.

The artisan moves along the length of the design embroidering the dank along.

Resources:

Mustan Zariwala – +91 98292 12052

Jewelled Textiles – Gold & Silver Embellished Cloth of India. (2015) – Vandana Bhandari. Om Books Publication

Handmade in India, Crafts of India – Edited by Aditi Ranjan and M P Ranjan. Mapin Publishing